Growing up in France

BECOMING FRENCH...

THIS IS HOW I FELT - AT FIRST

In September 1962, I was driven down to Grenoble (a town famous in 1815 for opening its gates to Napoleon on his way back from Elba) to do a year’s foreigners course at the University. Just sixteen, hopelessly naïve, I was deposited for safekeeping at Madame des Francs who ran a pension on the Rue de Tilsitt.

GRENOBLE AT THE FOOT OF THE FRENCH ALPS

A HOPEFUL 16

THE ROAD TO GRENOBLE

Large and infirm with skin like creased tissue paper, Madame des Francs received all daytime visitors in bed. She lay propped up, like Sarah Bernhardt, a cardigan over her nightdress, one bandaged leg (fibrositis, I later learned), resting like a frozen log on the counterpane. Obviously she had no interest in her foreign students. “L'argent s’il vous plait!’ she barked, when I walked in. All she wanted was the money.

SARAH BERNHARDT (MME. DES FRANCS)

The boarders were mainly English. There were three startled-looking young boys from minor public schools who, judging from their clothes—an assortment of fecal-colored tweeds—had never been farther than the home counties.

THE BOYS LOOKED LIKE THIS

There was an English girl like myself, and two American girls, whom Madame simply referred to as Les Americaines, respectful of their obvious wealth. Because one of the students hadn’t shown up, I managed to get a room of my own. It was on the top floor, down the hall from our communal bathroom with its rust rings decorating the porcelain. There were two sizeable beds (one missing a leg), a chair, a cracked marble fireplace, and an ancient light fixture with a single 40 watt bulb.

At first the boarders were all politely restrained at dinner. Then, after a week or so, we managed to get past our tame hellos by drinking Madame’s cheap red wine as fast as we could. The dining room had curved flaking walls. Also a concealed door––noticeable by a line of smudged finger marks––and was used solely by Mimi the maid who appeared from the kitchen at 8 o'clock with the food.

Madame herself always arrived late. We could hear her in the corridor; tap tapping like a blind woman, her stick preceding her. Eventually the double doors would crash open and she’d appear, like a battleship, listing to one side as she favored her good leg. We were all terrified. Even the American girls went quiet. And no one dared complain about the meals, which were memorable only because they were so bad: overcooked spaghetti, macaroni pudding. There was hardly any meat, except on Thursdays, when we had sauerkraut. This consisted of a bowl of vinegary cabbage topped by a few lethal sausages, large and so red that even the English boys considered them too scary-looking to be safe.

During that first week, one of the boys made a point of sitting next to me. About eighteen, Jeremy was tall, with a pale unformed face and a thatch of springy ginger hair––a wedge of wooliness that defied the comb. He leaned over, one Harris Tweed elbow sliding my way, ink stains dotting the sleeve. “I’m from Wales,” he announced. “Well, actually, my parents are. I’m frightful at languages. Can’t speak a word of French. In fact, I’m not overly endowed in the brain department, either. That’s why they sent me over here!” It was a cheery confession; his way of trying to open up to a girl. “Oh, really, ha ha,” I said. I was staring at his white hands, folded together on the tablecloth and looking, I thought, like dead fish. “Well, I suppose, we’re all here trying to learn something. A little savoire faire!”

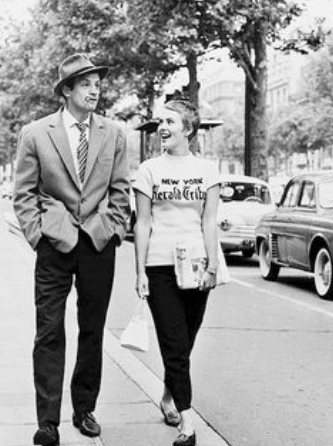

JEAN SEBERG - THIS IS WHAT I THOUGHT I LOOKED LIKE

I was haughty, anxious to sound sophisticated. I had cut my hair in a pixie bob, copying Jean Seberg’s in Au Bout de Souffle. It was too short for my round face and so to compensate I’d wrapped a new pink chiffon scarf ( bought for 5 francs at the local Galleries Lafayette) up to my ears. Every night, Jeremy sat next to me. I heard about his skin condition (nerves), his debutante sister, his mother’s love of geraniums. It was impossible not to like him; at the same time he represented everything I was dying to leave behind.

JEAN-PAUL BELMONDO AND JEAN SEBERG IN "BREATHLESS"

Most afternoons I spent on my own, in a back booth at the local café. I replaced my Marks and Spencer’s tartan kilt with a pair of navy corduroy trousers and a cream button-down crepe shirt–– thereby spending all eight pounds of my monthly allowance. I smoked Disc Bleu until my lungs ached, pretending to read the local paper, L’Isere, and drank endless cups of café aux lait. Occasionally, I ordered a croque monsieur from my friend Leon, the waiter, who kindly ran up a tab.

CROQUE MONSIEUR ( A TOASTED CHEESE AND HAM SANDWICH)

I knew nothing. I had a great feeling of importance about myself––though I had no idea where it came from. I was exhilarated, happy to be on my own. I started to bring a notebook with me to write down my “thoughts,” plus a copy of Jacques Prevert’s poems, which at sixteen I considered astonishingly insightful. Romance was constantly on my mind.

Cet amour

Si violent

Si fragile

Si tendre

Si desespere

THE FRENCH POET JACQUES PREVERT

Wrapped in this thin cloak of make-believe the future looked rosy.

Soon, romance. Yes - the inevitable affair with the foreigner....